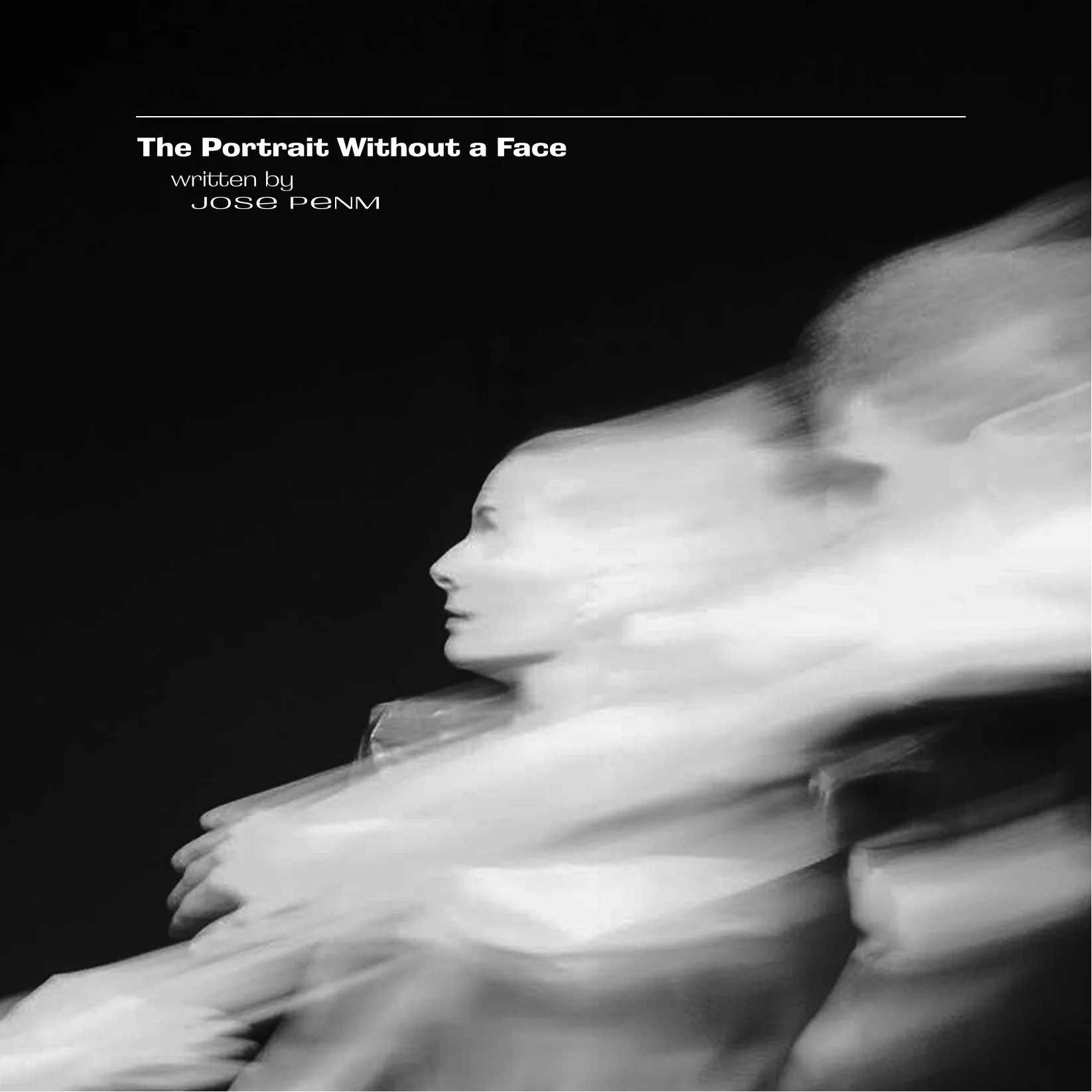

The Portrait Without a Face: Less Image, More Presence

© Jose Penm

A portrait can begin where the face ends.

In art photography we often treat the face as proof—an index of identity, a receipt of likeness. But presence is not a checklist of features. Presence is pressure in the room, the way a figure interrupts light and teaches it a new route.

A portrait, at its sharpest, is not documentation; it is measurement. Less image, more presence is not a slogan—it’s a working method.

© Jose Penm

That is why a portrait can remain a portrait when the face isn’t shown. The absence doesn’t erase the subject—it concentrates them. Like charcoal on paper, the black doesn’t describe; it holds.

The wall becomes a field of force, and the subject is read through what they bend: shadow, reflection, rhythm, posture, the small decisions of movement.

For years, the camera has been trained to hunt clarity. Commercial and documentary conventions reward the readable face, the immediate “who.” But in fine art photography, the decision can be different: to let light speak first.

Light is not decoration. Light is matter—tactile, exact, capable of being pressed into the sensor the way a line is pressed into a plate. When you trace it carefully, light carries more than skin. It carries tempo.

Think of a shoulder that catches a window at 4 p.m. The highlight is brief, polite, yet it reveals the angle of a day, the stiffness or ease of a body, the geometry of someone standing still.

A silhouette doesn’t hide; it edits. A reflection doesn’t lie; it rearranges. Motion blur is not a mistake—it’s a signature, a frequency shift that tells you how the subject occupies time.

© Jose Penm

This is where abstract photography and portraiture meet: not in obscurity, but in precision. The image becomes a fine art photo, photo art of presence—an identity articulated through what cannot be posed.

This is art fine photography: fine art and photography fused. When the face disappears, the viewer stops consuming and starts listening. The eye slows down. The room quiets. The photograph begins to breathe.

Try a small experiment.

Half-close your eyes and look at the person next to you. Then move your head side to side, as if your body were calibrating a lens. You’ll feel ridiculous for a few seconds. You may laugh. The moment loosens; it opens a seam.

Now stop. Don’t look again—check what stayed in memory.

It won’t be the face. It will be the posture, the tilt of the torso, the cadence of a gesture pressed into shadow, the rhythm of light along a sleeve. That is the portrait the mind keeps: not features, but presence.

This matters culturally because we are saturated with faces—endless images that promise intimacy and deliver consumption. The portrait without a face resists that economy. It asks for a slower ethics of looking, a curatorial dialogue rather than a scroll.

© Jose Penm

It invites institutions, galleries, and collectors to consider portraiture as an inquiry, not a product: museum-quality in intention, archival in its attention, exhibition-ready because it has structure, not spectacle.

A collectible work does not only survive in paper and pigment; it survives in meaning. Provenance begins with a decision: what you chose to make visible, and what you chose to withhold. In this approach, the withheld face is not avoidance—it is discipline. The line commands; the light testifies; the subject remains intact.

If this language of presence speaks to you, you can join the exclusive waiting list for the next limited edition collection, Honing the Line.

Join here: https://next.josepenm.com/honing-the-line (or reply with “WAITLIST” and you’ll be added personally).